Fulfilling Your Sample Size: What is Required and Why

May 2021 Issue

Author(s):

-

James Feldman, MD, MPH,

Chair of IRB Panel Blue

Introduction

Two new questions have been added to the INSPIR application:

At Initial Review: To request quantitative data demonstrating the feasibility of fulfilling sample size enrollment.

- At Continuing Review: To inquire whether any subjects have been enrolled in the past year; and if not, to request information on why no one was enrolled, and plans for increasing enrollment in the next year.

Why?

At Initial Review

The new question at initial review aims to minimize the likelihood that a study that involves human subjects and is greater than minimal risk will be approved when there is a very low probability that the required sample size will be reached. This question asks investigators to prospectively consider the feasibility of starting a study by confirming that there are a sufficient number of potential subjects at BMC/BUMC or its affiliates to fulfill enrollment.

Studies that involve human research subjects must be of sound scientific design in order to contribute to generalizable knowledge (45 CFR 46.111). Specifically:

“Risks to subjects are minimized: (i) By using procedures that are consistent with sound research design …and Risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result.”

This is especially important for studies that pose greater than minimal risk and do not afford the potential for direct benefit to the participants.

While the ethics of conducting underpowered research studies have been and continue to be debated1-7, it is both an ethical and scientific obligation to justify why a certain number of subjects are required for the research, and to inform potential subjects of this rationale. One perspective on this question is provided by Weinberg and Kleinman:

“Is there an adequate justification of the study sample size? From a scientific perspective, there should be enough subjects to address the study question and to ensure that the correct conclusion has been reached. From an ethical perspective, if there are too few subjects, the investigator cannot adequately address the study question: the power may be so small that the investigator would be unlikely to detect an extant effect. Thus, the risk to study subjects has served no purpose. In addition, the investigator may reach an incorrect conclusion regarding the study questions.” 4

Some authors have argued that underpowered studies could be justified in that the results could be included in systematic analyses or could provide an estimate for the effect size of an intervention. The authors of the CONSORT 10 statement summarized this debate5

“Some methodologists have written that so called underpowered trials may be acceptable because they could ultimately be combined in a systematic review and meta-analysis,(117) (118) (119) and because some information is better than no information. Of note, important caveats apply—such as the trial should be unbiased, reported properly, and published irrespective of the results, thereby becoming available for meta-analysis.(118) On the other hand, many medical researchers worry that underpowered trials with indeterminate results will remain unpublished and insist that all trials should individually have “sufficient power.” This debate will continue, and members of the CONSORT Group have varying views. Critically however, the debate and those views are immaterial to reporting a trial. Whatever the power of a trial, authors need to properly report their intended size with all their methods and assumptions.(118) That transparently reveals the power of the trial to readers and gives them a measure by which to assess whether the trial attained its planned size. (5)”

The CONSORT 2010 statement for required reporting of parallel group clinical trials indicates that there must be a rationale for the sample size estimate for a clinical trial. This justification must be based on the purpose of the trial and is directly related to the analytic approach (adaptive trial, superiority, equivalence or non-inferiority). As the CONSORT authors note5 :

“For scientific and ethical reasons, the sample size for a trial needs to be planned carefully, with a balance between medical and statistical considerations. Ideally, a study should be large enough to have a high probability (power) of detecting as statistically significant a clinically important difference of a given size if such a difference exists. The size of effect deemed important is inversely related to the sample size necessary to detect it; that is, large samples are necessary to detect small differences. Elements of the sample size calculation are (1) the estimated outcomes in each group (which implies the clinically important target difference between the intervention groups); (2) the authors should indicate how the sample size was determined. If a formal power calculation was used, the authors should identify the primary outcome on which the calculation was based (see iyem 6a), all the quantities used in the calculation, and the resulting target sample size per study group. It is preferable to quote the expected result in the control group and the difference between the groups one would not like to overlook. Alternatively, authors could present the percentage with the event or mean for each group used in their calculations. Details should be given of any allowance made for attrition or non-compliance during the study.5”

Recruitment and retention of research subjects has also been recognized by the National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Research (NCATS) as an important scientific and ethical concern.8

NCATS states that,

“Creating safe and effective treatments, diagnostic tools and medical devices that improve human health requires successful testing of those interventions in humans. Researchers nationwide face common barriers in recruiting (or accruing) enough participants for clinical trials. The inability to identify and recruit the right number and type of people to participate often:

- Makes clinical trials slow and more costly;

- Limits the validity of trial results and, in turn, researchers’ ability to apply the findings broadly to the general population; and

- Stops a trial prematurely or prevents it from taking place at all.

In fact, a recent analysis of more than 7,500 Phase II and III cancer trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov between 2005 and 2011 found that 20 percent were never completed. The most common reason: inability to recruit participants.”

There could be many explanations for the sample size justification in INSPIR Section 14.1. For pilot exploratory or feasibility studies, the sample size could be based on testing the feasibility of the proposed study procedures in a small number of participants or providing an estimate of an outcome.9 While underpowered studies could potentially contribute to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, this is a complex and debated justification for starting a study that is likely to fail to meet the sample size required.10

The major ethical concern is that a study that poses greater than minimal risk without the potential of providing direct benefit to the participants will not reach the required sample size. This exposes subjects to risk without benefit.

There could be many reasons why a study will not reach the required sample size. Potential subjects may refuse to participate or drop out at a higher-than-expected rate; a protocol may be too complex; or there could be other factors that limit enrollment. However, one major potentially preventable concern is where the target population (at BMC, BUSM or wherever the study is planned) is known to be inadequate.

The risk of beginning a research study that is likely not to meet the required sample size is especially problematic in investigator-initiated single center clinical trials that are greater than minimal risk. For example, planning an interventional trial that requires 100 participants to test a new medication in a population with an illness that is very rare at BMC or its affiliates could be anticipated to be difficult to complete.

While this concern is considered less ethically problematic in multicenter research where BMC/BUMC investigators are contributing to a larger study (assuming the parent study meets the required sample size), there could be scenarios where the recruitment at BU/BMC could be a concern. For example, consider a 3-site study where each center is expected to contribute 200 subjects in a 2-year period where only 10 subjects were enrolled at BU/BMC during the first year. Here, failure to meet the required sample size locally could threaten the ultimate success of the study.

As a result of these concerns, the electronic IRB INSPIR application has been modified to collect data on the size of the potential subject pool. The objective of this new form in INSPIR is that that the IRB now requires the Principal Investigator to provide both a rationale for the sample size for a study; and there must be a quantitative estimate that supports the feasibility of the research. This rationale must be explained during the informed consent process to a potential subject (i.e., “You are being asked to be in a study that is just beginning to test drug X or intervention Y”; or “You are being asked to be in a study to see whether drug/device/procedure X will improve the outcome of the disease/condition”).

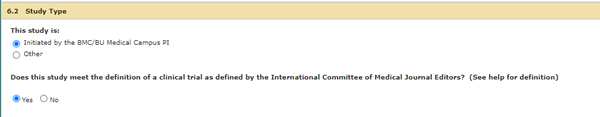

For studies that are checked off as BMC/BU Medical Campus investigator-initiated clinical trials in the Funding section:

And Single-Site:

Section 9.1 Single Site research:

a NEW question will appear.

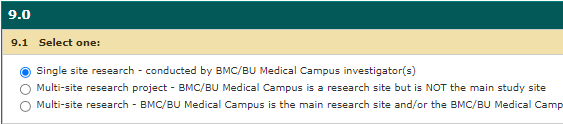

The Sample Size Justification section will now include the following:

NEW QUESTION (This will appear if all 3 of the above (Investigator-initiated, clinical trial, single-site) are checked off):

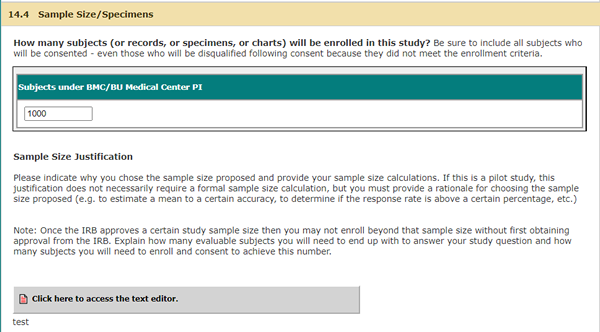

You must provide data to justify how you will have access to a population that will allow recruitment of the necessary number of subjects. In order to approve this study, the IRB has to determine that scientific design is sound, and that the study has the potential to contribute to generalizable knowledge. Consistent and statistically meaningful enrollment is necessary to support a positive risk-benefit ratio. Arriving at an answer to the study question in a timely fashion is integral to justifying the risks taken by the subjects and the time they spend participating in the study. It allows for realization of the potential benefits of the research, and maintains temporal scientific relevance of the study question itself.

Please indicate which service you have used to obtain quantitative data regarding the potential number of eligible subjects.

Select all that apply:

[Textbox]

Please provide data demonstrating the feasibility of enrolling your sample size:

[Textbox to Answer Question]

This is how the revised Sample Size section will now look in INSPIR for these studies:

Going forward, for all other types of studies, the following text will appear:

Describe how you will have access to a population that will allow you to fulfill recruitment of your proposed sample size. Please provide quantitative data.

[Textbox to Answer Question]

The BU CTSI will provide resources and support through the Research Navigator Team and other Cores to aid investigators in the recruitment of subjects to successfully meet the required sample size. Depending on the specific study, other approaches to increasing recruitment could include (if appropriate) adding another site; considering whether the protocol should be revised (i.e., eligibility, study procedures); or early termination (with reporting of results). Please contact the CTSI at the following link: https://www.bu.edu/ctsi/support-for-research/the-research-navigator-team/.

At Continuing Review

The IRB is also adding this question to the CONTINUING REVIEW form:

Have you enrolled any participants in the last year?

[If No]

Consistent and statistically meaningful enrollment is necessary to maintain this study's overall positive risk-benefit ratio. Arriving at an answer to the study question in a timely fashion is integral to justifying the risks taken by the subjects. It allows for realization of the potential benefits of the research, and maintains temporal scientific relevance of the study question itself.

In the text box below, please explain the circumstances that contributed to the lack of enrollment in the last year, and describe your plan to improve enrollment going forward.[Textbox]

This is being added for the same reasons discussed above; namely, as part of the continuing review, it is the IRB’s responsibility to determine whether the approval criteria for the study remain met. If the study has little to no chance of every fulfilling enrollment and/or reaching a meaningful conclusion, the risk/benefit ratio analysis for the study may no longer support its continuation.

References:

- Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, Braunholtz D, Jackson J. Why "underpowered" trials are not necessarily unethical. Lancet. 1997 Sep 13;350(9080):804-7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02290-3. PMID: 9298015.

- Halpern SD, Karlawish JH, Berlin JA. The continuing unethical conduct of underpowered clinical trials. JAMA. 2002 Jul 17;288(3):358-62. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.358. PMID: 12117401

- Rosoff, Philip M. “Can Underpowered Clinical Trials Be Justified?” IRB: Ethics & Human Research, vol. 26, no. 3, 2004, pp. 16–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3563753. Accessed 19 May 2021.

- Weinberg JM, Kleinman KP. Good study design and analysis plans as features of ethical research with humans. IRB. 2003 Sep-Oct;25(5):11-4. PMID: 14870739.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11:32. Published 2010 Mar 24. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-11-32

- Peter Bacchetti, Leslie E. Wolf, Mark R. Segal, Charles E. McCulloch, Ethics and Sample Size, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 161, Issue 2, 15 January 2005, Pages 105–110, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi014

- IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. Obtaining evidence by a single well-powered trial or several modestly powered trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016 Apr;25(2):538-52. doi: 10.1177/0962280212461098. Epub 2012 Oct 14. PMID: 23070590.

- https://ncats.nih.gov/pubs/features/ctsa-act

- Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, Lancaster GA. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010 Jul 16;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-67. PMID: 20637084; PMCID: PMC2912920.

- Turner RM, Bird SM, Higgins JP. The impact of study size on meta-analyses: examination of underpowered studies in Cochrane reviews. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59202. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059202

.